Cities, SI Urban 2/2021, Tourism

Mobility pricing – Modern financing for transport

One winning formula for mobility pricing can be found in Switzerland. There, through mobility pricing, the federal highways agency hopes to get people to switch from cars to public transport. “In Switzerland, the railway accounts for 15 percent of transport capacity, which makes us number 1 in the world.

Yet private motorised transport still accounts for 75 percent of our traffic,” Jürg Röthlisberger, Director the Swiss federal highways agency, outlines the problem at Salzburger Verkehrstagen transport conference. Congestion periods are increasing year on year and each one causes a billion francs of damage.

Another “problem”: the progressive decarbonisation of transport is continuously reducing state revenue from tax on mineral oil. “Mobility pricing can replace both this and similar taxes and duties as well as preventing road congestion and promoting environmental conservation,” Jürg Röthlisberger emphasises.

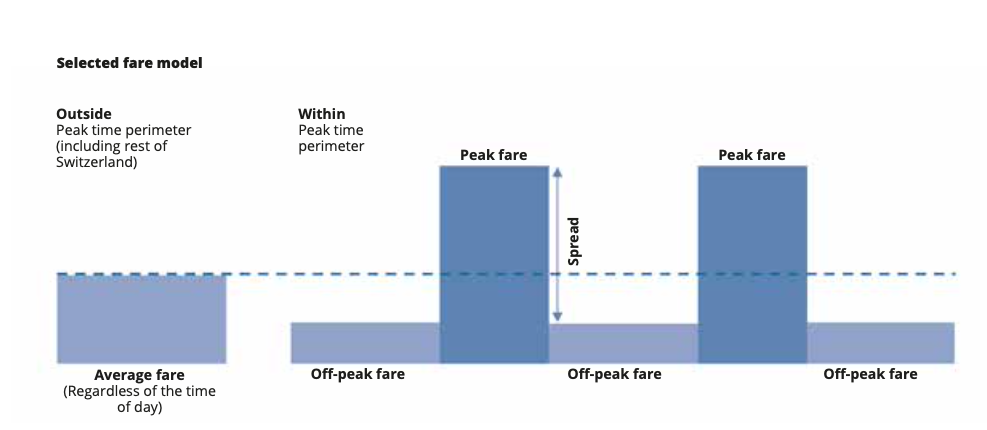

Essentially, mobility pricing has two elements: first, prices based on distance travelled across the country (kilometre charges); second, time- differentiated prices in areas with severe traffic congestion (peak time perimeters).

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF MOBILITY PRICING

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF MOBILITY PRICING

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bonus/penalty model

“Peak time perimeters are defined on the basis of urban, city landscapes and affect two hours respectively in the morning (7.00 to 9.00) and in the evening (5.00 to 7.00),” Röthlisberger says. The director of the federal agency emphasises that the peak times are identical in both private and local public transport.

The key to mobility pricing is a fare model with a sort of “bonus/penalty” within the peak time perimeter. In addition to the average fare, this means there is a more expensive peak fare and a cheaper off-peak fare.

“We hope that this spread will encourage people not to travel during the rush hour, whether by public transport or in their own car,” Röthlisberger says. The aim is that only those who have to will travel in peak times.

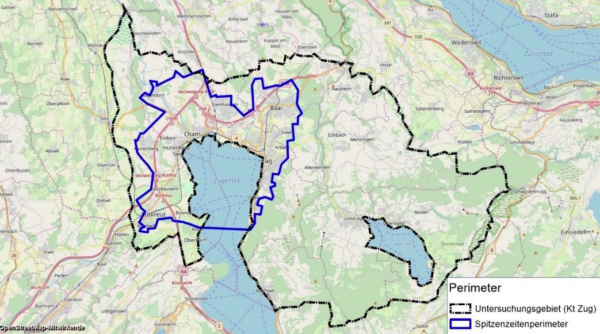

Mobility pricing based on the example of the urban area of Zug, with the peak time perimeter (outlined in blue) and study area (outlined in black). Diagrams: INFRAS

Effect on traffic

The effect of mobility pricing on the volume of traffic was clear to see in the model calculation for the Swiss urbanareaofZug:atpeaktimes,the volume of car traffic decreased by nine to twelve percent and the volume on public transport fell by five to nine percent.

“By sorting out the volume of traffic, travel on public transport becomes more comfortable. Tight cycle times during rush hour and journeys on demand during off-peak times become possible,” Röthlisberger explains. In turn, drivers gain greater time reliability, as they have little congestion to worry about.

Distribution effect

However, it is also clear that mobility pricing has consequences for people’s pockets. It replaces not only taxes and dutiesbutalsopreviouslyconventional transport charges.

Whilst the strain is eased for budgets with time flexibility, the burden is borne by inflexible budgets, which generally affect the lower income bracket.

Yet, even in the worst-case scenario, no more than 0.9 percent is added to gross household income, Röthlisberger emphasises: “With mobility pricing, mobility also remains affordable for most people.

For inflexible budgets in the lowest income bracket, there is certainly a risk of problematic additional costs under certain circumstances. However, these could be reduced through targeted conceptual adjustments.”

Further effects

No negative side effects on other areas were identified. On the contrary: “We see slight positive effects on spatial development and the economy. For example, delivery and service traffic is no longer stuck in congestion,” the director of the federal agency says. Not least, mobility pricing has noticeable positive effects on air pollutant and greenhouse gas emissions. ts