Cable Car Radio, Cities, SI-Urban

Urban cable cars: chances and challenges

Mr. Monheim, could you tell us about some of the most interesting urban cable car projects currently underway in Germany?

Heiner Monheim: One new project in Duisburg involves a longer cable car that will connect four different areas, where urban development and cable car development go hand in hand. The most developed project is certainly the one in Bonn, where a cable car system is planned to connect with three main rail routes. This project is very close to the planning approval phase and the actual construction start. It has already had ten years of discussions behind it.

Then there is an interesting project in Herne, where a small cable car system is planned to open up a new development area behind the main station. This is a typical project that we actually need much more of, because we often have new development areas.

A new theme park is being built, a new residential area is emerging, along with large retail spaces. These areas are always accessible only by road, close to a city highway, and poorly connected, if at all, by a bit of bus traffic. This is exactly the kind of situation where we need more cable car projects.

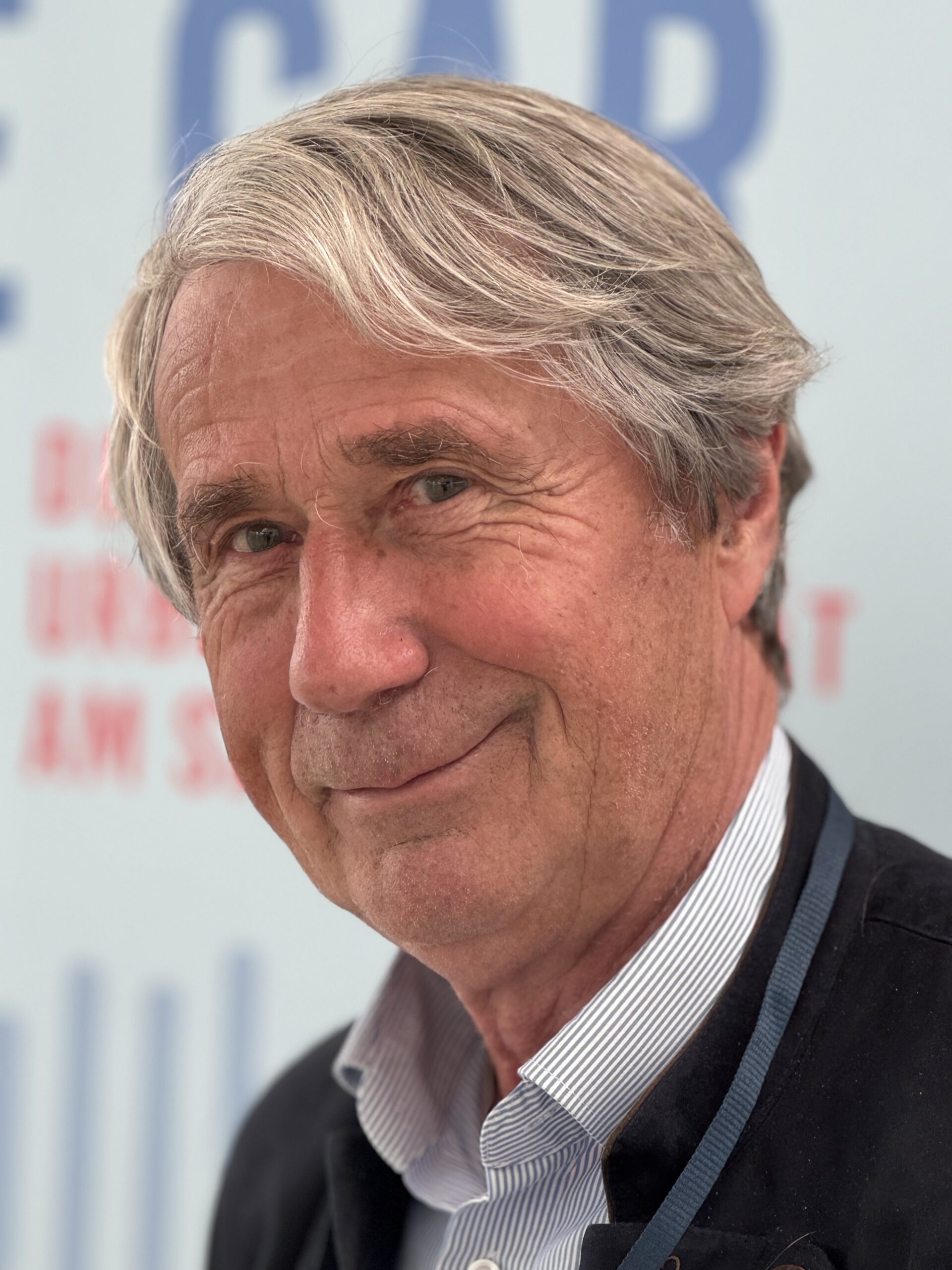

Heiner Monheim

Heiner Monheim is a geographer, urban planner, and transportation expert, bridging the gap between academia and practice. From 1995 to 2011, he served as a professor of Applied Geography, Regional Development, and Land Planning at the University of Trier. With immense passion and dedication, he has spent many years advocating for more livable cities, better public transport, and modern, innovative transportation policies.

You’ve been working in the field of urban cable cars for over 40 years. What has changed in these 40 years?

Forty years ago, people were considered crazy if they even talked about cable cars outside of the Alps. It was always clear: cable cars were for winter sports, requiring high mountains and snow. It took a long time before it was accepted that cable cars could also be interesting in flatland areas.

For example, at Expo Hannover, there were no Alps, but we still built a cable car. The same for the Buga in Rostock—no mountains, yet we built a cable car there. Gradually, it became clear that cable cars can also work effectively in flat areas, with the significant advantage of requiring minimal infrastructure. You need towers, stations, and the rest is just cables and cabins.

So, it’s relatively cost-effective and quick to set up. Essentially, the infrastructure of a cable car can be reused multiple times, which you can’t do with a road or a railway line. This is a very specific sustainability advantage of cable cars.

And when you compare it to roads and rail, the footprint of a cable car is much smaller.

Yes, of course, it’s minimally invasive. I don’t need to flatten everything for it; I just need towers at certain intervals and stations. The issue of stations is still treated somewhat amateurishly. When we have cable car debates in Germany or Austria, the architects often want to build a huge, expensive structure that makes the project unfeasible. We need the simple, everyday cable car station.

In Germany, the only good example is the Berlin Cable Car, where the mountain station is built with minimal construction effort. It’s just there casually, it works, and that’s all it needs to do. It’s similar to a tram stop. That’s how we need to approach the cable car topic.

We need to try to place the stations at ground level as often as possible, so we don’t have to deal with costly elevators and escalators, which have high operating costs and are prone to breakdowns. The goal should be to keep it as simple and straightforward as possible.

This also gives a cost advantage compared to the subway.

Yes, of course. A typical tram station costs about 5% of the investment required for a subway station. A cable car station is a bit more expensive than a regular tram station, but it shouldn’t be massive.

The cable car at the Gardens of the World:

This cable car in Berlin operates between the Kienberg subway station and the visitor center of the Gardens of the World.

Has the “Guideline for Urban Cable Cars” facilitated the planning process?

A lot of practical experience has gone into it. On one hand, it familiarizes people with the basics—such as the differences between various types of cable cars. Then, it also provides a lot of practical, administrative help. How do you best plan a cable car system?

Unfortunately, in Germany, we are still far from this. The cable car projects currently being discussed are more or less accidental. They don’t emerge from a long search process, like how to best solve traffic issues. Instead, some politician raises their hand and says, “I want a cable car here”.

And then they start working on that one project without having a master plan or a strategy for how to expand public transport — which urgently needs to be done from a climate policy standpoint—in the most efficient and cost-effective way. We still lack that. We need much more of that. And the guideline definitely highlights the point that you need to do proper preliminary and conceptual planning before diving into the details.

When could the first urban cable car in Germany be built, integrated into public transport and the fare system?

My great hope is that, after a long wait, the project in Bonn will finally move forward, as it’s now relatively well-developed with political commitments and decisions already in place. The famous planning approval process means that, from my perspective, it will be five years too late, as it could have progressed faster.

Once it’s up and running, I hope it will have a certain momentum, inspiring similar projects that are two or three years behind, giving them a boost. By 2035, we should have five or six similar projects in place.

It’s also very important to note that some projects, like the Koblenz cable car, are very successful and in high demand, but it’s not integrated into public transport. It has a separate fare system, and its connection to the public transport network is poorly designed. Getting to the final stations with other modes of transport is very complicated.

If public transport integration had been considered from the beginning, it would have been possible to connect the cable car to the train line in Koblenz, near the main station or the central city stop. But because of time pressure, this wasn’t achieved in the planning process.

Additionally, there’s a larger redevelopment area at the top of the mountain near the Ehrenbreitstein Fortress, where the cable car should sensibly be extended. I’ve been advocating for this for years, but unfortunately, Germany is very slow when it comes to implementing such solutions.

The Koblenz cable car is more than just a tourist attraction.

Since June 2010, it has connected the Rhine promenade near St. Kastor Basilica with the plateau in front of Ehrenbreitstein Fortress.

What could Germany do to overcome this inertia?

First of all, the famous standardized evaluation system—the cost-benefit analysis procedure—needs to be urgently revised, and it must lead to actionable results. Very often, despite being designed for economic efficiency, these evaluations end up leading to extremely expensive nonsense.

A lot of tunnel projects come out of it, and one wonders how this can be considered economically viable when the project takes 15 years to complete, costing hundreds of millions, or even a billion, like in Stuttgart. We are simply stuck with this „tunnel virus“, because underground there are no conflicts.

No one protests when you dig a big hole. However, it’s actually misguided, because it’s extremely unreasonable to invest in such expensive projects when much faster and more cost-effective solutions could be implemented above ground.

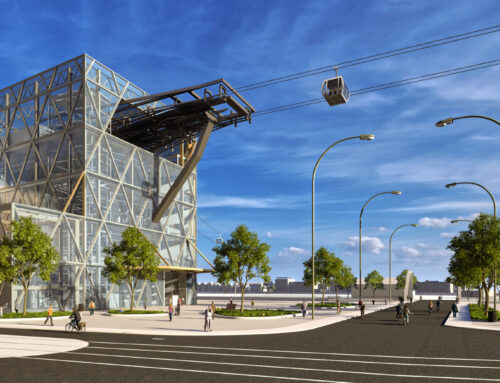

Best Practice Bonn:

In the city of Bonn, a large majority of residents support the cable car because a well-thought-out concept has been developed there.

How important do you see architecture for the success of an urban cable car?

It really depends on the environment. I believe the greatest potential for cable cars—and the greatest need — is in suburban areas. On the outskirts of cities, we usually have plenty of open space. There are large distances between buildings, wide roads like urban highways or multi-lane streets.

Suburban areas also have the highest development dynamics, with new residential areas constantly being built. Many cable car projects should be implemented there, and there’s no need to build grand, cathedral-like stations. Simple and functional stations would be perfectly fine.

I also believe we’ll only make progress if investors start changing their mindset and begin to think not just in terms of cars, but primarily in terms of public transport, and then contribute to these investments. This is the difference to France. In France, there’s a legal framework with a local transport tax that businesses must pay. This is why we’re seeing many interesting tram and cable car projects emerging in France right now.

We don’t have that here. We only have it for car traffic. Investors have to contribute to the infrastructure for car traffic, at least for the internal connections. But public transport doesn’t even factor into their plans. That has to change. The lawmaker needs to step in here.

In general, public transport funding in Germany is completely underfunded. We spend far more money on car traffic, new roadways, and parking garages. That’s why the legal and fiscal framework needs to change urgently. Right now, municipalities are largely overwhelmed and can’t do what they’d actually like to do, which is make the transition to sustainable transport a reality.

Transparency Notice:

Interview conducted by Gerald Pichlmair. This article is an edited transcript of the German-language podcast Cable Car Radio.